Saki's From Zero to Hero Romhacking Guide Part 3: An Example through Magical Date

This post will likely be the final part of my series of posts that aims to de-obfsucate and demistify romhacking. It will also be quite different from the previous ones, since I think that I explained enough general concepts for anyone who doesn't understand what I'm talking about to reread either the part where I explain C & Assembly or the one about Debugging & Reverse Engineering.

If you don't care about the writings and want to give a look at the actual code, you can consult the source code for the project (and some documentation related to it) on my GitHub.

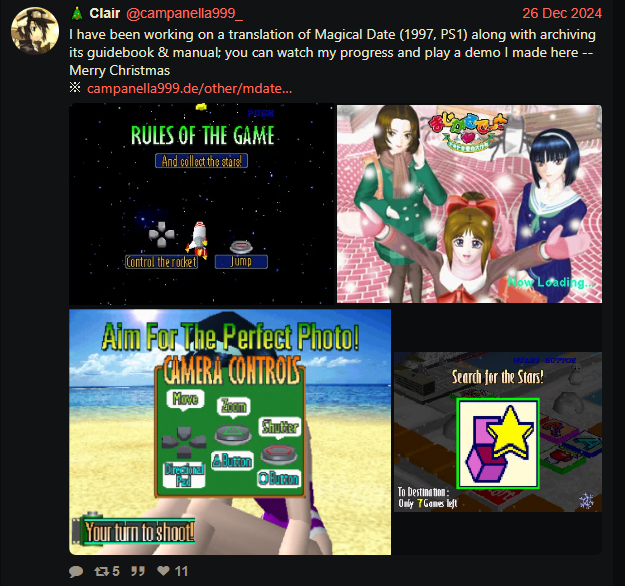

Somewhere around April 2024, Clair, whom I was friends with since at least a year, reached out to me with quite the interesting project in mind: what if we were to collaborate on the translation

of an obscure Taito party game I had never heard about before ? On paper, it sounded fun enough.

As some of you may know, I've always daydreamed about releasing translation patches for

games. I still cling to my amateurish Silver Case translation to French, sometimes going as far as putting it on my CV whenever applying for jobs,

and same goes for the TGM:Ace English patch, which barely serves a purpose since we're talking about Tetris, a game everyone and their grandma could understand.

Even then, there is something nice about helping people break through the linguistic barrier and attempting to bring a wider audience to any kind of work, whether it's a novel, a movie, or a video game,

but the technical challenges that stand in the way of a game's translation and all the knowledge one acquires while working their way through said challenges make it even more thrilling.

Another motivation about the project back then was that I had fallen in love with ZUNTATA's works around that time, so naturally Magical Date would immediately catch my attention for being such a...

forgotten Taito title.

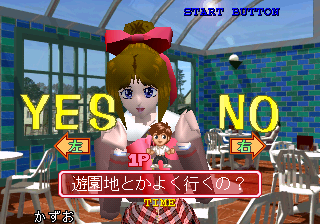

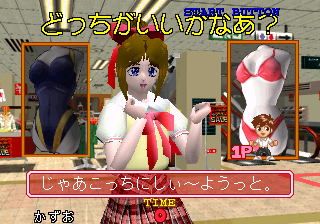

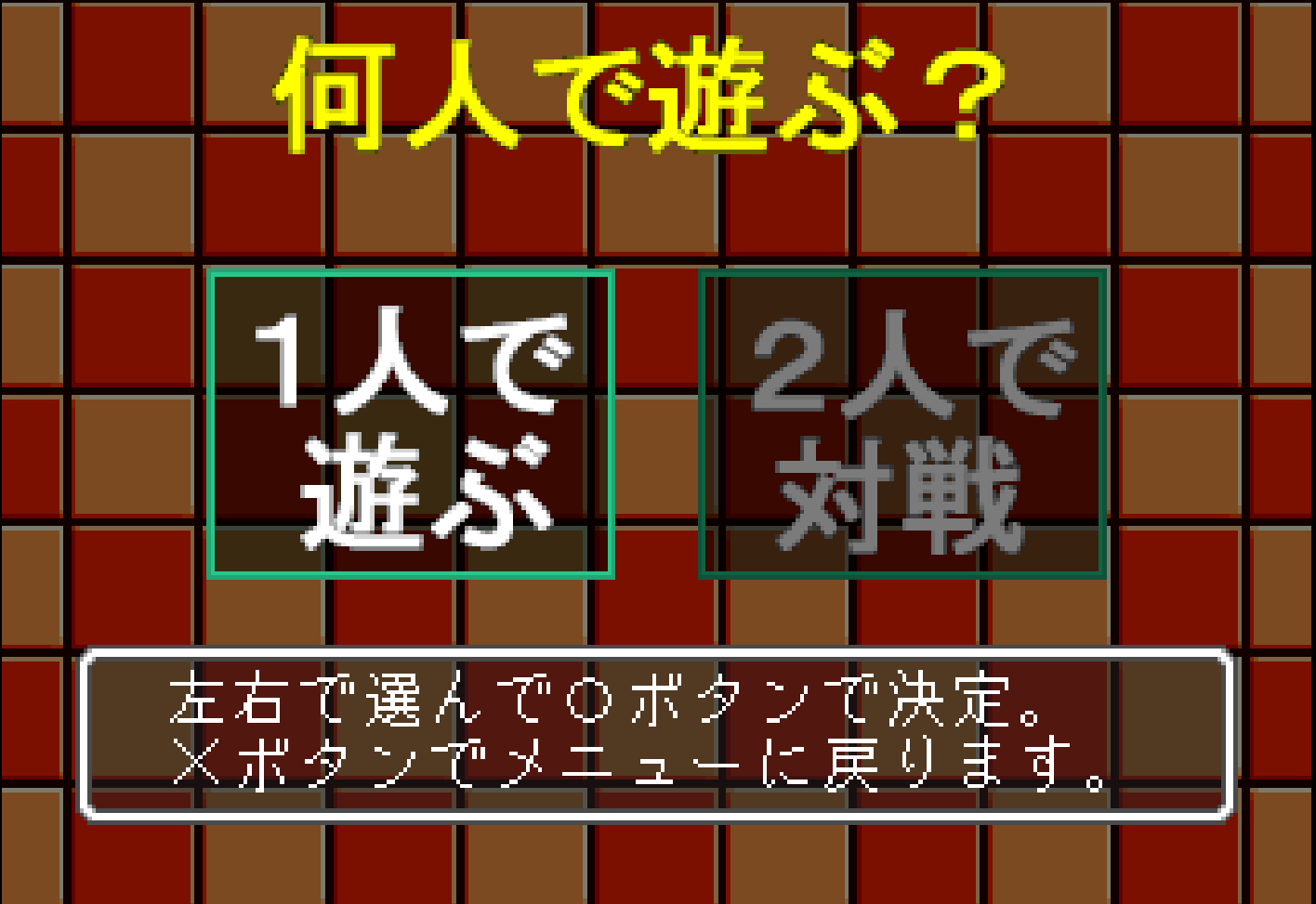

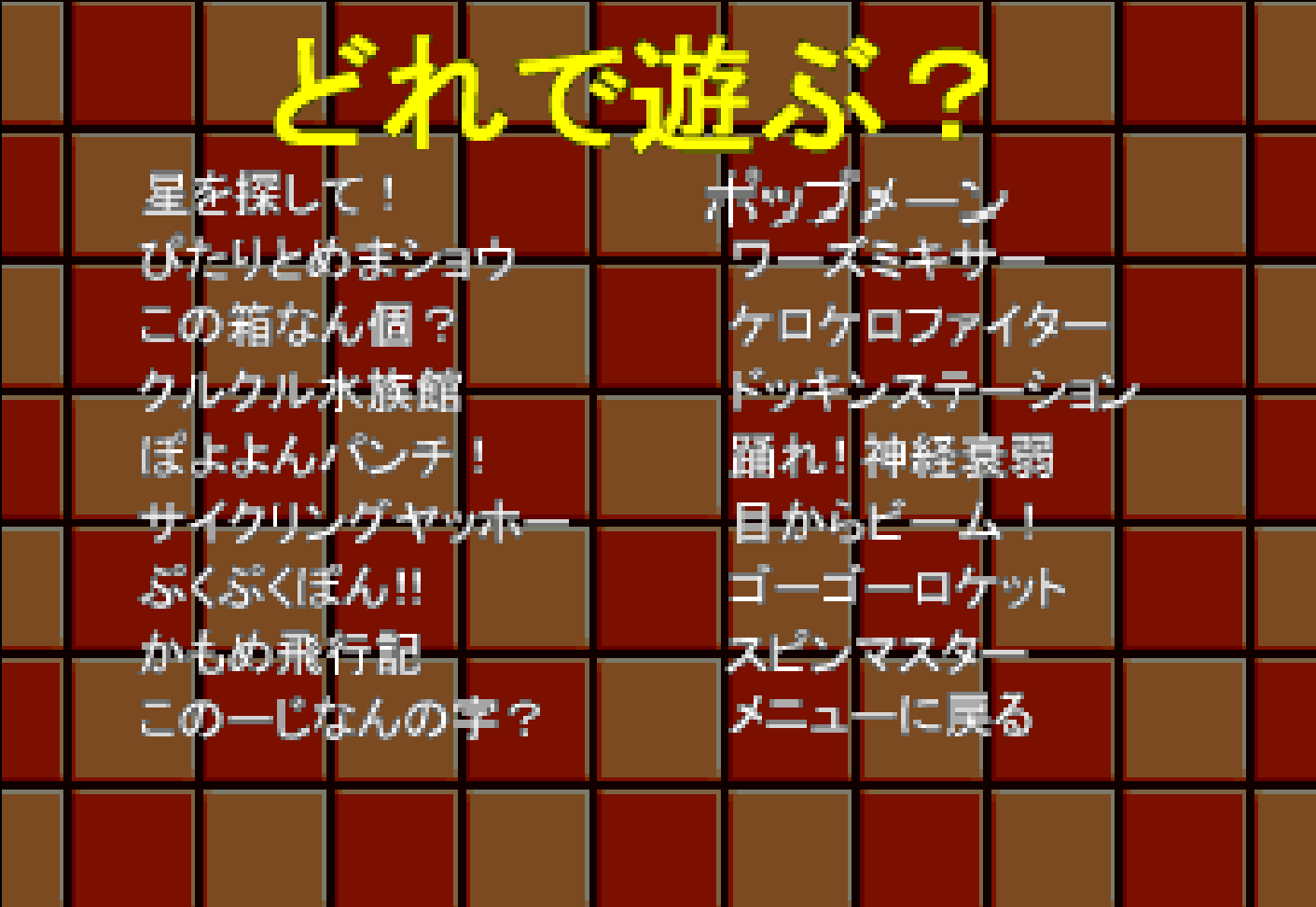

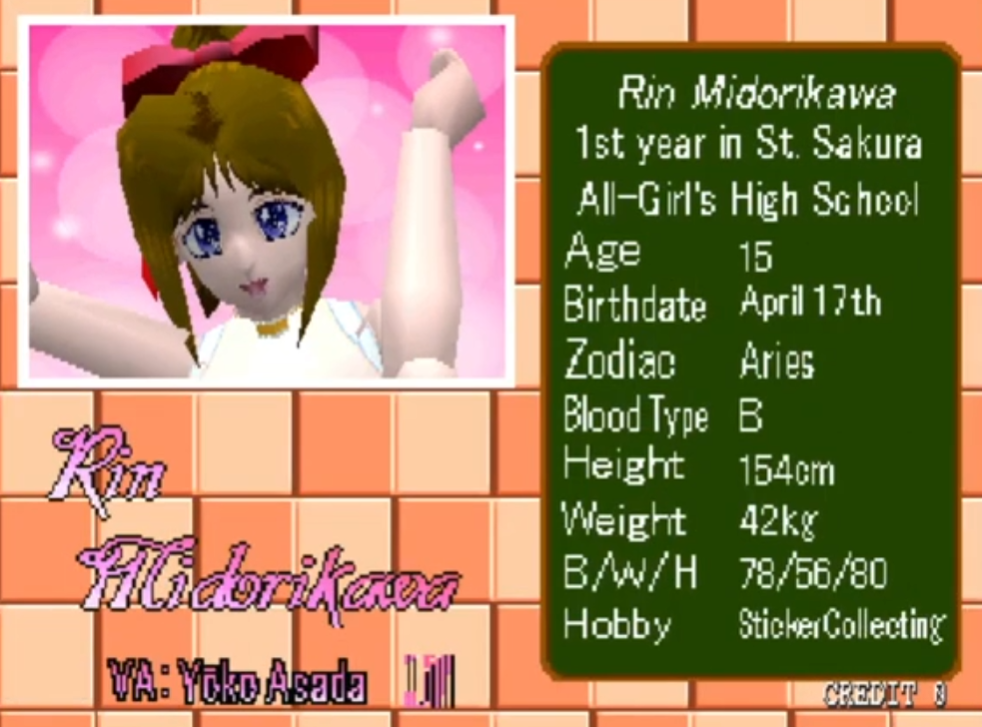

I was familiar with Taito's works from the mid-late 90s such as the Ray series, Darius, Puchi Carat, Arkanoid Returns, Elevator Action Returns, hell I had even exchanged about the obscure Gamera 2000 with Clair before, but Magical Date? I didn't even have an idea of what it could be about! I was asked to watch some footage of the game, and, like it's probably the case for any westoid who'd be made aware of its' existence, I was surprised to see that, while it did indeed have some "dating", the game mostly revolved around clearing minigames on a board (not unlike a WarioWare or a Gun Bullet). The girls seemed quite talkative, always giving little comments about the player's skill level after clearing a minigame, and there seemed to be some sections in-between two minigames where you'd get to speak to the girl directly and answer some questions, pick an outfit for her, or take photos of your (soon to be?) girlfriend with the outfit you had selected before. Each of those breaks had a fair amount of talking, not a lot, but enough to make me wonder about what was said, especially since the player doesn't have the luxury of choosing whenever the text would appear or go away: after all, it's initially an arcade title, you can't keep the other clients waiting on the cabinet forever.

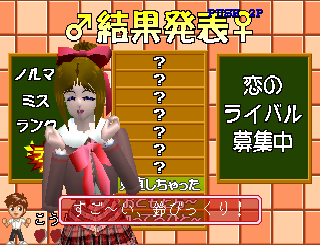

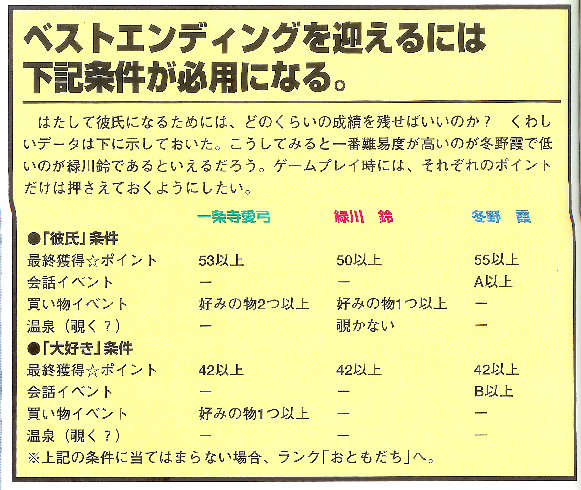

Eventually, I gave the game a try myself, and that's when it dawned upon me: as Taito loved doing it back then, Magical Date features arank system, which is depicted with Stars on the recap screen after clearing each minigame. If you suck at those quizzes, the girl will more likely than not end up heartbroken, and your final game rank will suffer in consequence. Later, thanks to the Strategy Guide, Clair confirmed to me that each girl can give you either the "BOY FRIEND", the "SWEETHEART", or the "KISS" ending, and that those endings depended not only on the player's ability to clear the minigames, but also some specific conditions such as the rank you obtain when the girl quizzes you or how many of the outfits you picked ended up to the girl's liking. There was a clear incentive to make the game "playable" for the EOPs of my kind now!

Enough playing around, now was the time to dig into the game's files! This is when we gathered many tools that'd help us extract and manipulate the files. Since this post is still supposed to be about romhacking, and learning how to do so, let us go through the toolset we've made for ourselves, and what each tool was for. This will be quite the long ride, so feel free to skip a few sections if you care more about how we started playing around with Ghidra and PCSX-Redux's debugger.

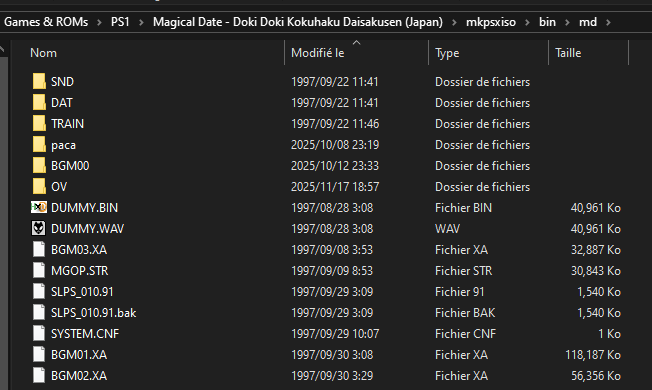

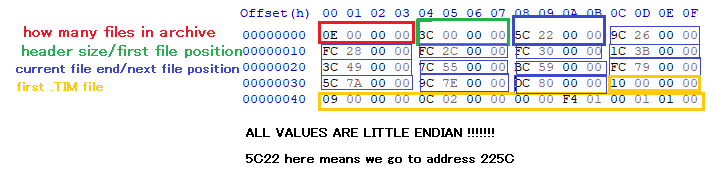

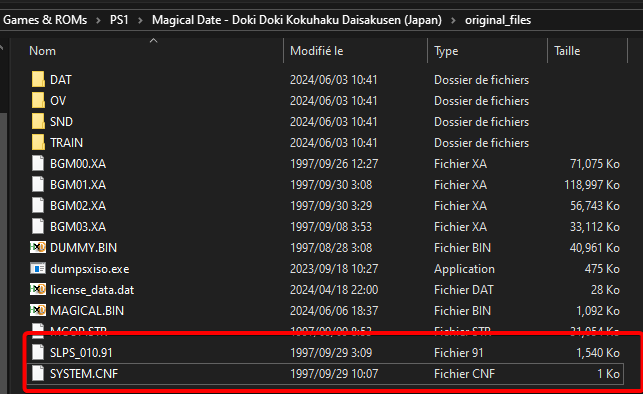

First, we needed a way to extract and rebuild the game's disc structure. Thankfully, this is nowadays an easy task, thanks to Lameguy64's mkpsxiso/dumpsxiso toolset. You dump the contents of a bin/iso with dumpsxiso, which gives you a nice folder arborescence and an .xml file that contains the structure of the disc. Said XML can then be used to rebuild the folder back to the bin/iso format with mkpsxiso.

The extracted files had some formats I was personally familiar with.

I knew that .XA files were related to the game's audio, and that MGOP.STR, given both the name and the extension, was likely the game's opening cutscene. These formats can both be decrypted to more common ones

with jPSXdec, as I explained so previously in a post of mine.

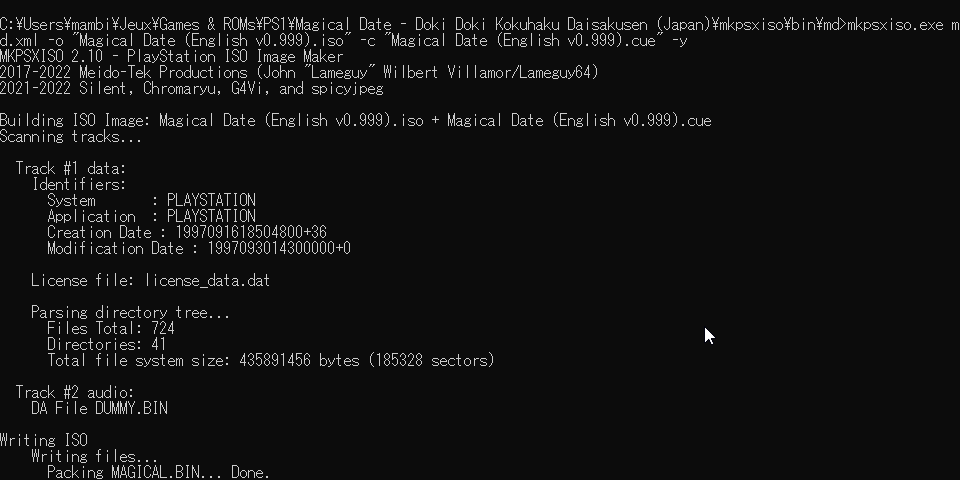

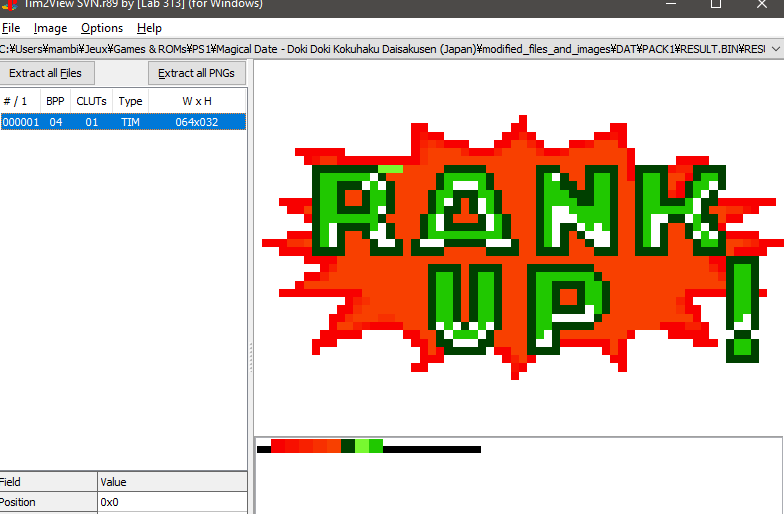

Then, we had ".TIM" files, which we weren't that familiar with before starting to work on the translation, but we'd heard some things about it from Hilltop's videos about PS1 graphics, notably

that it was the go-to file format for storing images on the console.

After some searching, it turned out that Tim2View was able to analyze files and load their TIM data, and even export them as PNG, or individual TIMs in case of an archive made of multiple BINs.

We will get to the details later, but this was already enough for Clair to get working: we had found dozens of sprites to redo from Japanese to English, mostly names you'd see on the map and menus, and now we had them all as PNG... Hurray?

The task was about to get daunting, the sprites apparently had to be redone by hand to look any convincing/close to the original style, no sane person would decide to do such a thing, but thankfully Clair was crazy enough to do exactly that.

By the way, Tim2View's "Import PNG" feature kept breaking the sprites but the TIM Reimportation worked quite well, so we introduced a little middleman, another tool by Lameguy64, img2tim,

which can convert any image to .TIM.

As such, our workflow was the following: extract all sprites as PNG, edit them by hand, convert to .TIM, import back into the game with Tim2View.

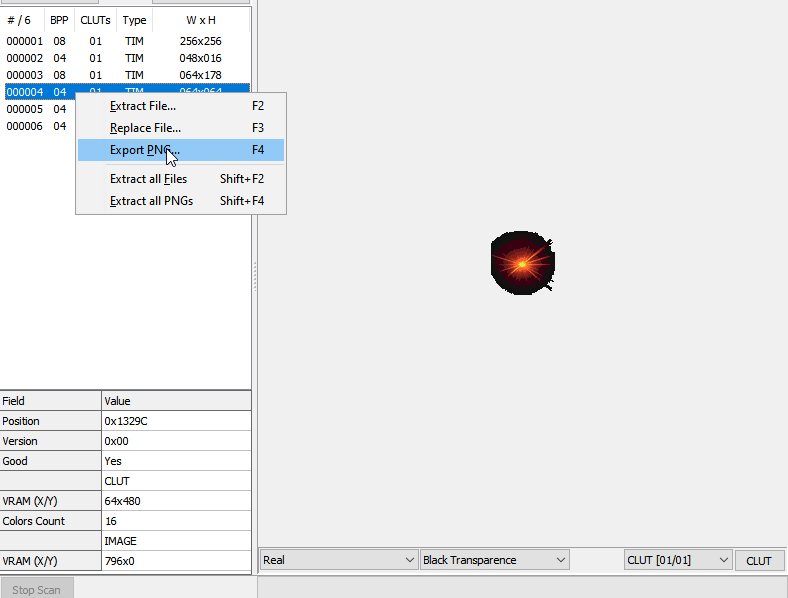

At some point, Clair needed to have the height of a particular TIM file expanded, doubling it in size. This would usually be no big deal, but it posed a problem to us: most of the game's TIMs were contained inside of, very basic but still existent, .BIN archives. Said archives' format is pretty easy to explain, I had made an explanatory screenshot of it back then, and a BIN Repacker Python3 script which would reinsert a .TIM right where it belongs. Making and debugging this script took about half a week, and this was probably the moment when it was kind of naturally imposed upon me to handle the translation's technical aspects from then on, and for Clair to do the translation and sprite editing work I would never ever be qualified for even if I tried.

From here on, please keep in mind that while I was deep in the datamining and reverse engineering trenches, Clair was smoothly proceeding with the game's graphical editing, so even though the progress was slow on the technical side, the general progress of the project was pretty constant... For now.

Anyway, about the technical part earlier... Since we now had a way of editing .BIN files containing sprites, this effectively meant that Clair could go full gear with the graphical work. I, on the other hand, had a tremendous task assigned: it was up to me to reverse engineer and understand enough of Magical Date to make it possible to insert English into a game which at first glance only seemed to accept Japanese text encoded with Shift-JIS. That's right, it was Ghidra time, but not only. Strap in, this will be a long one!

Since we didn't feel very confident about being able to crack a PS1 game open, Clair and I spent a lot of time looking up existing resources about the PS1, the file formats commonly used on the console, how the RAM is ordered, the MIPS assembly it uses, and much more.

...

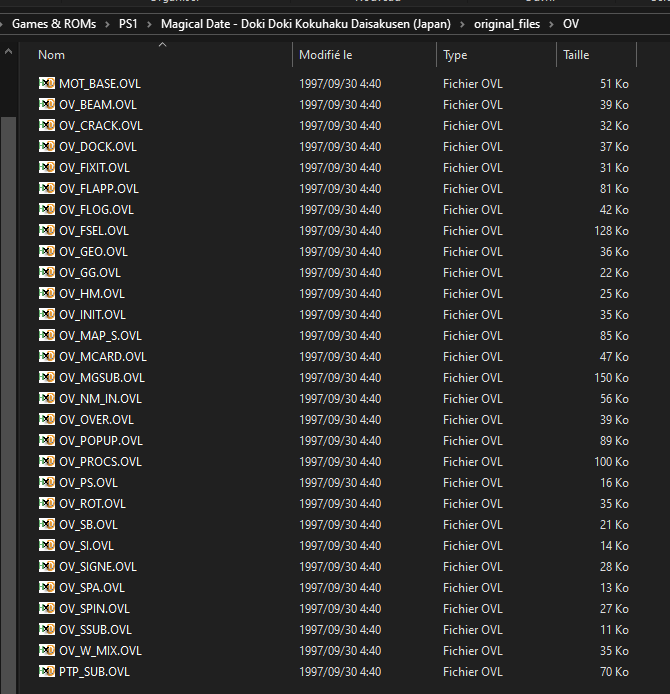

Okay, truth be told, we didn't get to the technicalities on our own right away. Our first main lead was Tetracorp's series of posts about the analysis of TokiMemo: Forever With You since it's also a PS1 game. The first post alone introduced us to a Ghidra PSX Plugin, the general process of "renaming stuff until the code makes sense", the PS1's Memory Map and how it begins at 0x80000000 rather than 0x0, and even the concept of Overlays, which wasn't super clear from that one post alone, but gave me a lead about what to look for next. We'll get back to the rest later, but that piece of information was eye-opening since the game features an "OV" folder, inside of which were .OVL files that didn't seem to be archives of any kind.

At this point, we were yet to do any static analysus or debugging, it sounded reasonable to keep looking at each file by ourselves and see what obvious truth could be inferred from that alone. Since .XA and .STR files

were already explained before, we'll focus on the remaining files.

There was a license_data.dat file. Such a file tells the console which region a disc comes from, and in case of mismatch will reject the disc altogether. It's not super important for us but fun fact: at some point I

managed to put an NTSC license file instead of the japanese one, which caused the game to make both my PS3 and PS1 freeze during the testing even though the game worked flawlessly on emulators. It took me a couple days to

figure it out...

There were also couple .BIN files at the root of our game which didn't seem to contain any image. The first one was a DUMMY.BIN file, which was just 45MB of padding, a seemingly common anti-piracy measure back then.

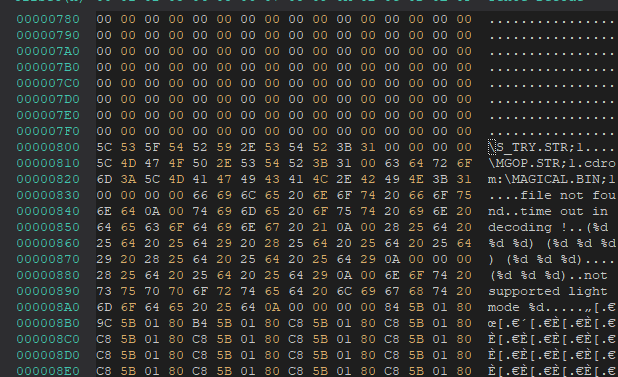

The second one was MAGICAL.BIN, we will get to that one soon.

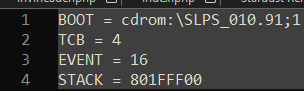

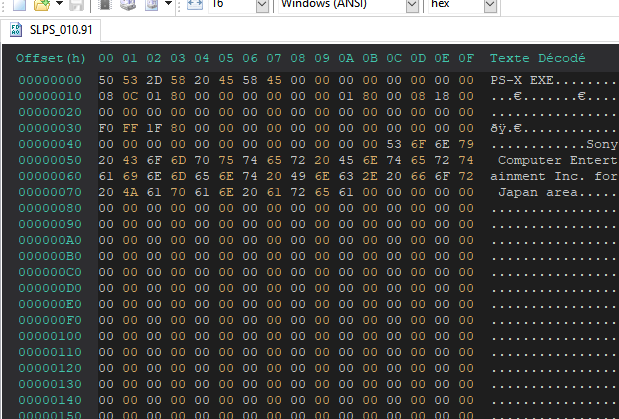

It's fairly common knowledge that for retail games, the "main" executable is named after the game's ID, and sure enough, in our game's fles' root lies an SLPS_010.91 file, which corroborates with the

contents from the descriptive SYSTEM.CNF file alongside it.

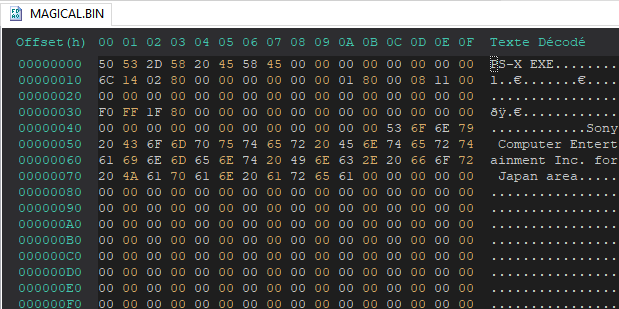

This executable file was... Weird, to say the least. For some reason, even though its' size was 1.50MB, half of this space was zeroed out, almost as if it was only there for padding purposes. It definitely was an executable since, as zanneth's post about PS-X EXE files says, the file started with the "PS-X EXE" magic bytes, followed by some information related to the executable, then "Sony Computer Entertainment Inc. for Japan area", and finally, zeroed-out bytes of padding until we'd reach 0x800.

You might have noticed on the last screenshot, but that executable acknowledges MAGICAL.BIN's existence, so we might as well open that file to see what it's about and... That's when something unexpected happens. This seemingly innocent .BIN file had the signature of an executable... What could this possibly mean?

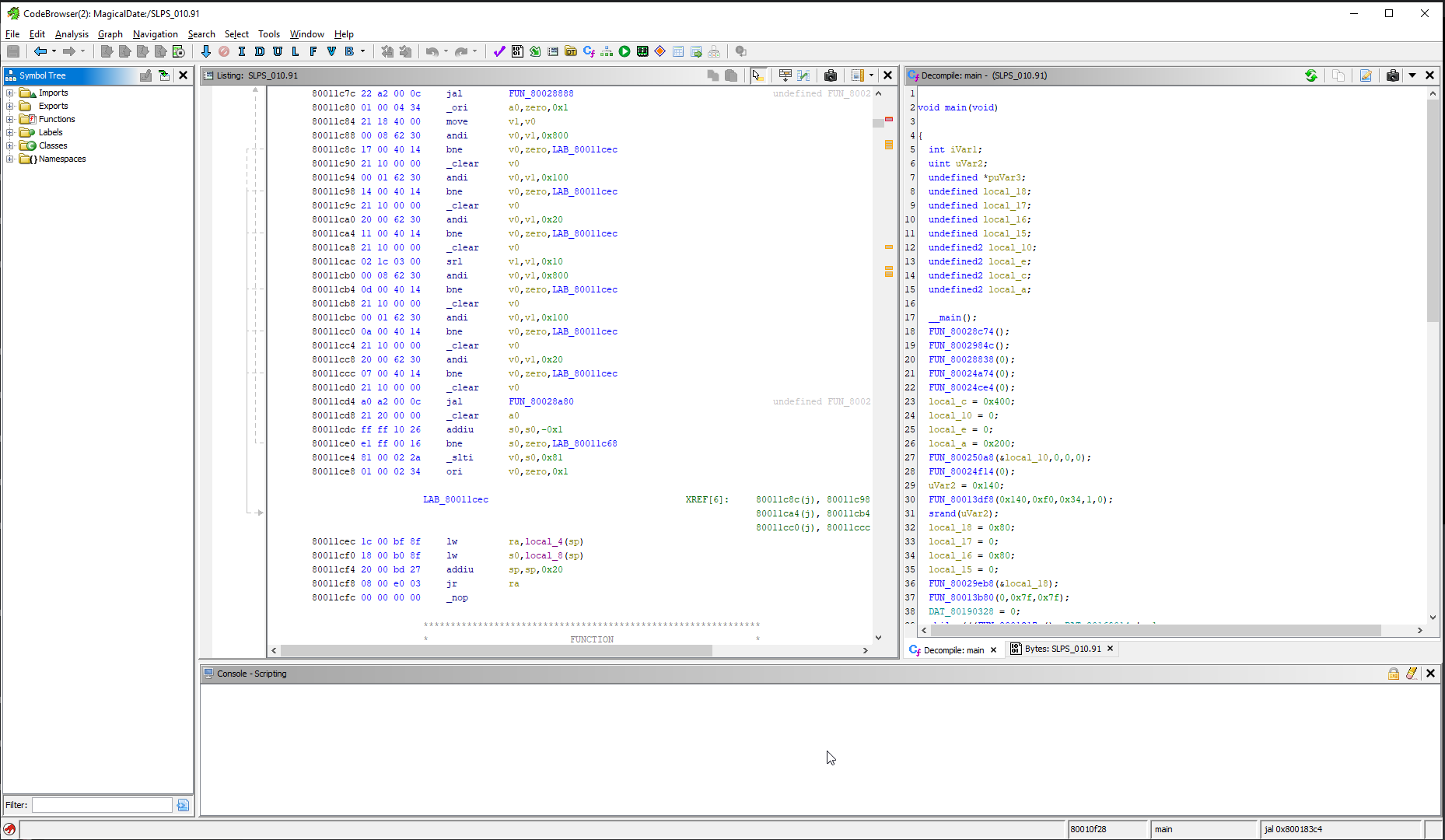

There is only so much guesswork we can do simply by looking at the files, it's time to let computers do their job so let's open up Ghidra, install the PSX extension, and throw both of our executables into the thing. We're going to analyze the SLPS_010.91 file first since it's supposed to be the main executable. Fortunately enough, ghidra focuses the main window into the main function as soon as the analysis is over, so we can get to the interesting part right away.

Honestly speaking, we don't know much about what this "main" executable does, and I will explain why right now. You see, when you boot up the game, it plays an opening FMV again and again until you press the credit button (SELECT).

Once you do press that button, the game puts you into the attract mode at first, then on the main menu if you insert another credit. There is absolutely no way for the player to rewatch the FMV unless they reboot the game. Finishing the game

brings you back to attract mode, getting a game over brings you back to attract mode, pressing "EXIT" on the main menu brings you back to attract mode. What gives ?

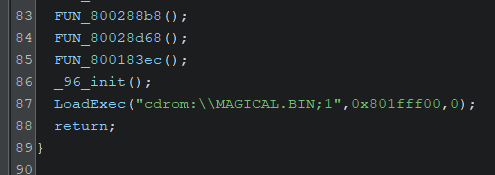

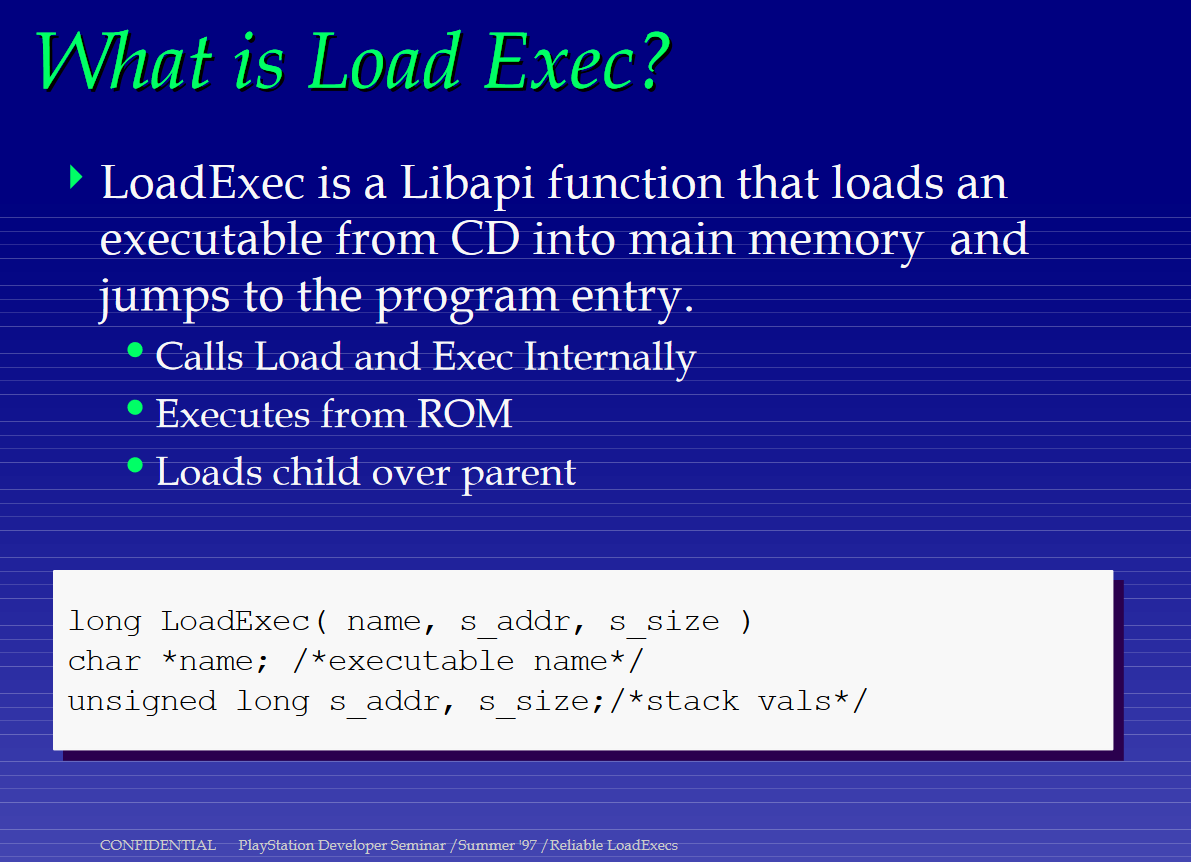

If we investigate further, we notice that our SLPS file's code isn't that big. There is a while loop which involves our opening FMV file, but most importantly, there is a LoadExec instruction at the bottom of the file that refers

to our mysterious MAGICAL.BIN file, and that's where everything clicks together.

Alright, this will require some explanation, but since the PS1 (Psy-Q) SDK's documentation has been made available online, searching up that function name gives us a very detailed slideshow which explains to developers its' purpose and usage. From this document, we learn that LoadExec, as its' name indicates, loads an executable into memory. It is often used to segment stages into separated executables, for demos, or, you guessed it, "cinematic sequences". It also says some stuff about overlays, but we'll get to that later. Finally, it mentions that _96_init() must be called, which our executable does, so there is no doubt about the usage of that function: what I referred to as the "main" executable is nothing but a program made to load the main opening, likely because storing the FMV and the rest of the executable data was not possible in a way that would make the whole game fit into 2MB.

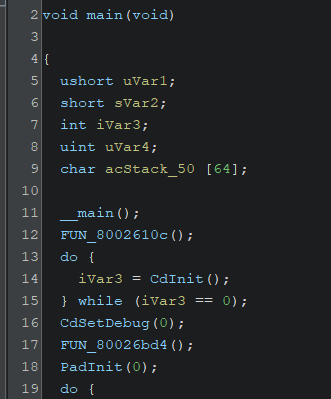

Well, let's see if MAGICAL.BIN is as easy to deal with then, what do we have in the main function ? Something about initializing the Cd and the Pad... a sprintf call (???), and an infinite loop... Yeah, this is as far as we could go with static analysis. Let's find an emulator that has breakpoints (preferrably all kinds of them but an execution breakpoint would be a good start), and try seeing which functions do what by setting breakpoints at all the FUN_address locations.

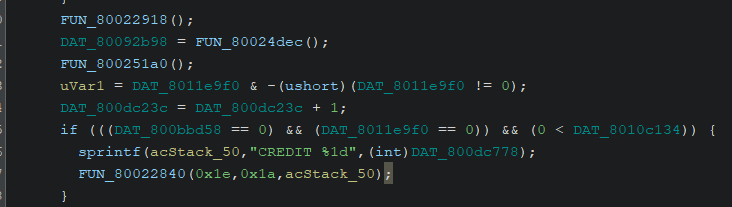

I wasn't really looking forward to this part, honestly speaking. Whenever I work on any program, my "debugging" could be summed up as a minefield of printfs and condition checks, so working with an actual debugger sounded scary at first. I found a 2010 guide on the matter that sounded good enough, gathered my courage, and started looking for a PSX Emulator that would feature advanced enough debugging tools. It would probably not be ePSXe, and even though no$psx and pcsx were seemingly used a lot for debugging purposes, I wanted an emulator which would either be extremely robust in its' debugging features, or one that would have decent debugging features and be widely used by your average emulation enthusiast. More explicitly, I was split between Duckstation (which I probably don't need to introduce) and PCSX-Redux, a fairly niche emulator made with reverse engineers and PSX devs in mind. I tried going with the former, but Duckstation's debugging features are really... not there.

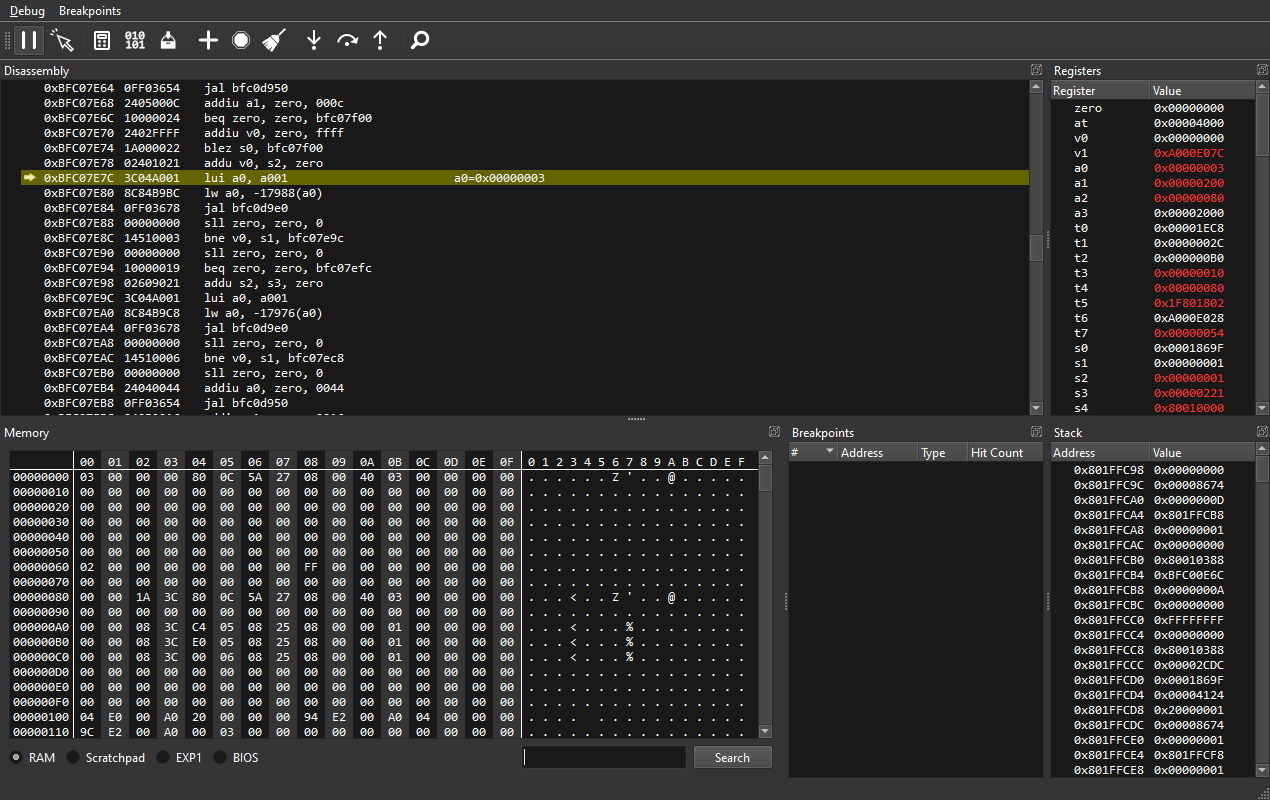

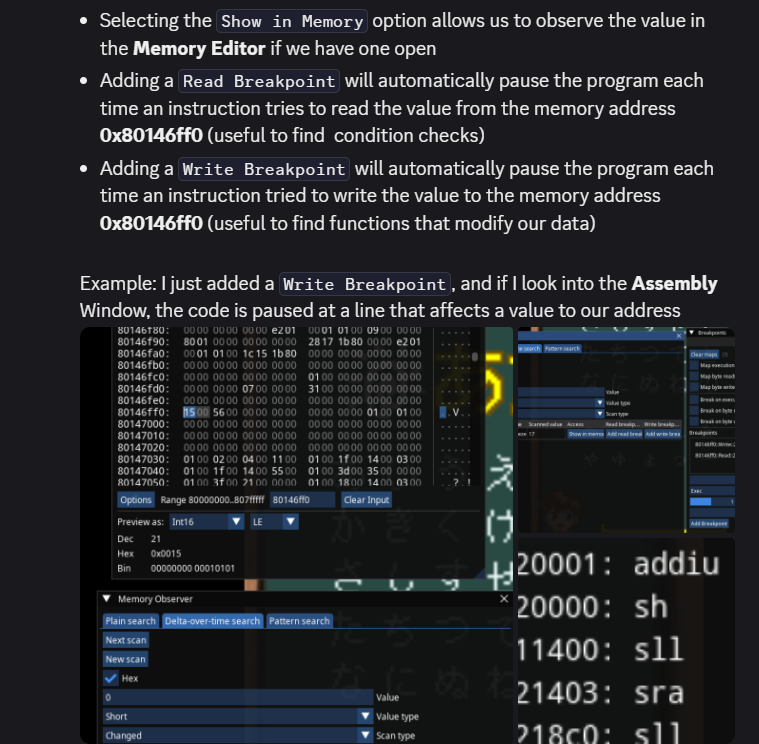

Anyone who used Cheat Engine before knows how memory observers work: you scan the program's current memory, then you do something specific, then you look for changed values, rinse and repeat until you filtered out all the "irrelevant" data. When you only have a dozen candidates left or less, you start editing those memory locations, and hoping they'll do what you'd expect them to. I was having lots of fun taking notes about the process and showing Clair that I was indeed doing more than fruitlessly opening Ghidra and blankly staring at functions I understood nothing about lol

So that's how the debugging went: looking for interesting values in memory with the observer, finding which functions act on them, analyzing those functions in Ghidra at the same time in hopes of understanding how everything works better. At that point there wasn't helping it, we had to learn how PSX-related MIPS Assembly is standardized, most importantly which registers would be used for what but also which operations were available.

So, a few paragraphs above, I very confidently stated that the game accepts Shift-JIS encoded text. How could I know that ? Well, Ghidra can scan for Encoded Strings, and SJIS is part of the supported charsets, so that solves the matter, doesn't it ?

Nope. Back when we started the project, we very obliviously used Ghidra's 10.3.1 release, as the PSX plugin's latest public version at the time didn't go above that.

I had to ask a kind soul on the PSX.DEV Discord to compile the extension for the 11.0.2 version later on, but for now we were just playing with the cards we were given.

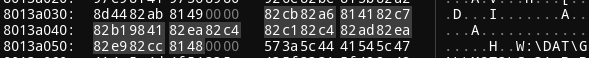

Anyway, this doesn't really answer the question: how did I know? Well, someone made a web-app which could convert hexadecimal code to Shift-JIS,

and vice versa. So I took a bunch of bytes that looked like text out of the game's memory, and ran it through the converter to obtain the Shift-JIS data, and it sure was

the same sentence as what the game was showing me.

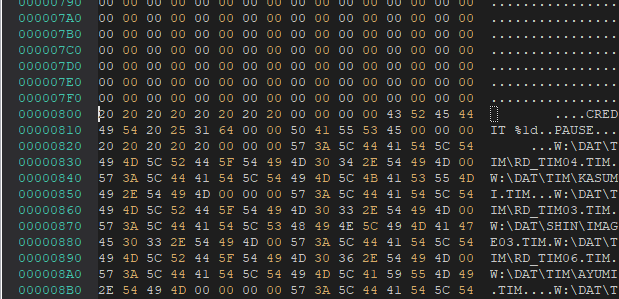

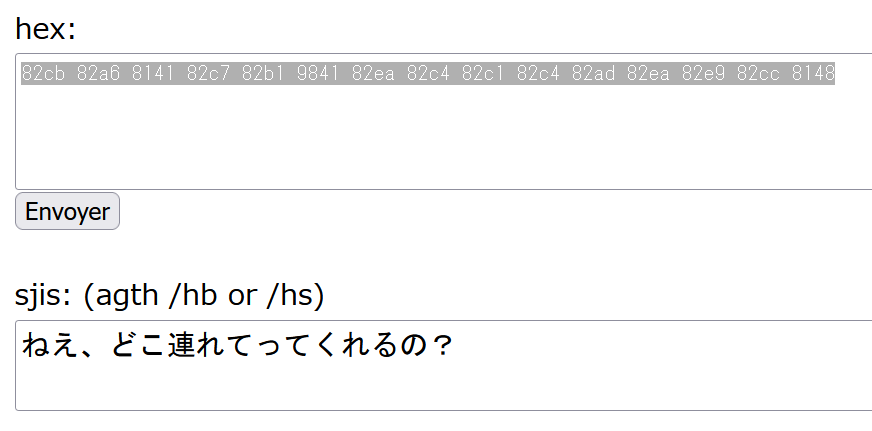

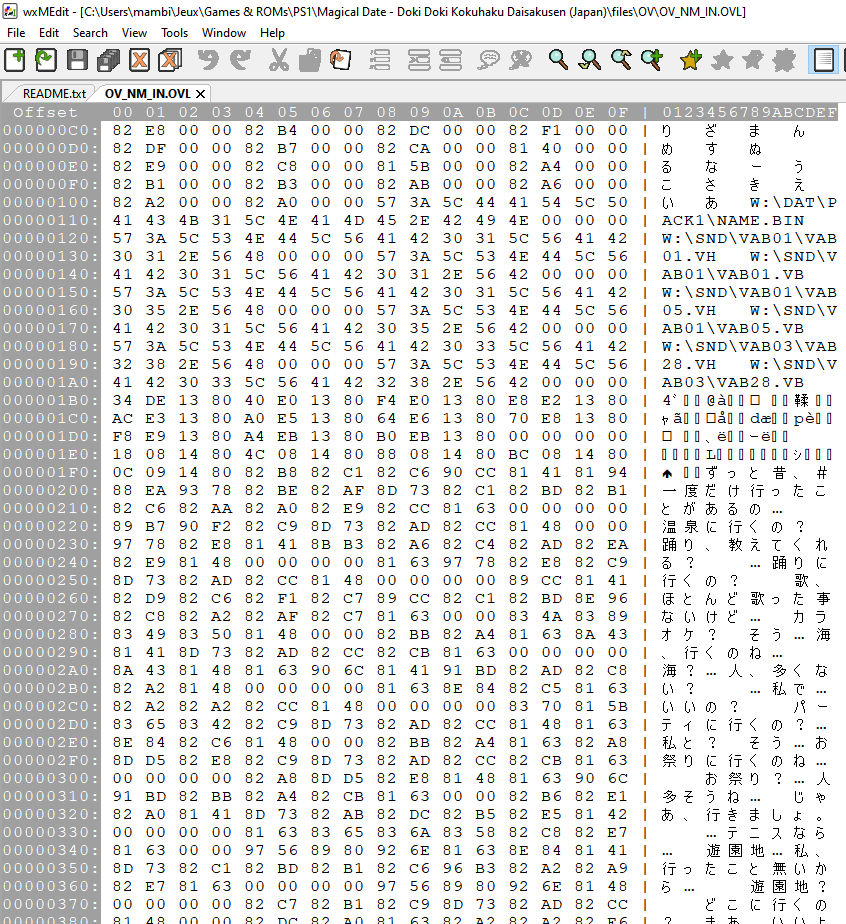

After solving that huge mystery, I decided to look up all of the game's files to find out where the bytes of text come from in the first place. After a little grepping, I had found my match, an .OVL file in the "OV" folder.

At that moment, I remembered about the TokiMemo guy mentioning something about overlays being

additional executables, which would match with sony's documentation. Overlay files are binaries you can load on the fly into the RAM, and

they don't even have to take over/replace the main executable. There was a slight catch now though: how do I tell Ghidra about that ? Since Overlays are "injected" into a specific location in the RAM, you can't easily infer

their alignment in memory unlike it'd be the case with a conventional executable.

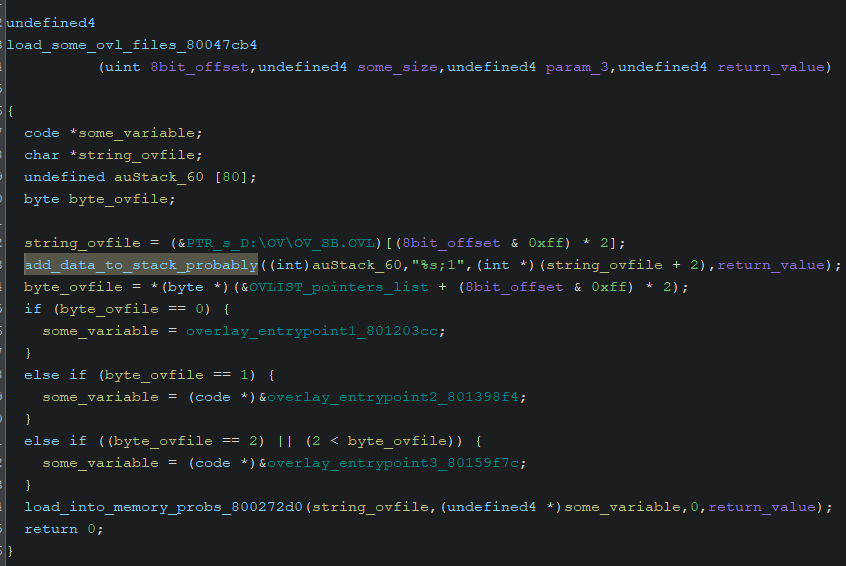

No worries, ghidra_psx_ldr's creator made a video about this exact process. It turns out all you have to do is to "just" find a function where the game would look up

those files from the CD, and there'd likely be a function that would load those files into a specific RAM area after locating them. After enough analysis and variable renaming,

I had found all the places where the game would load its' overlays, and which ones would be loaded where.

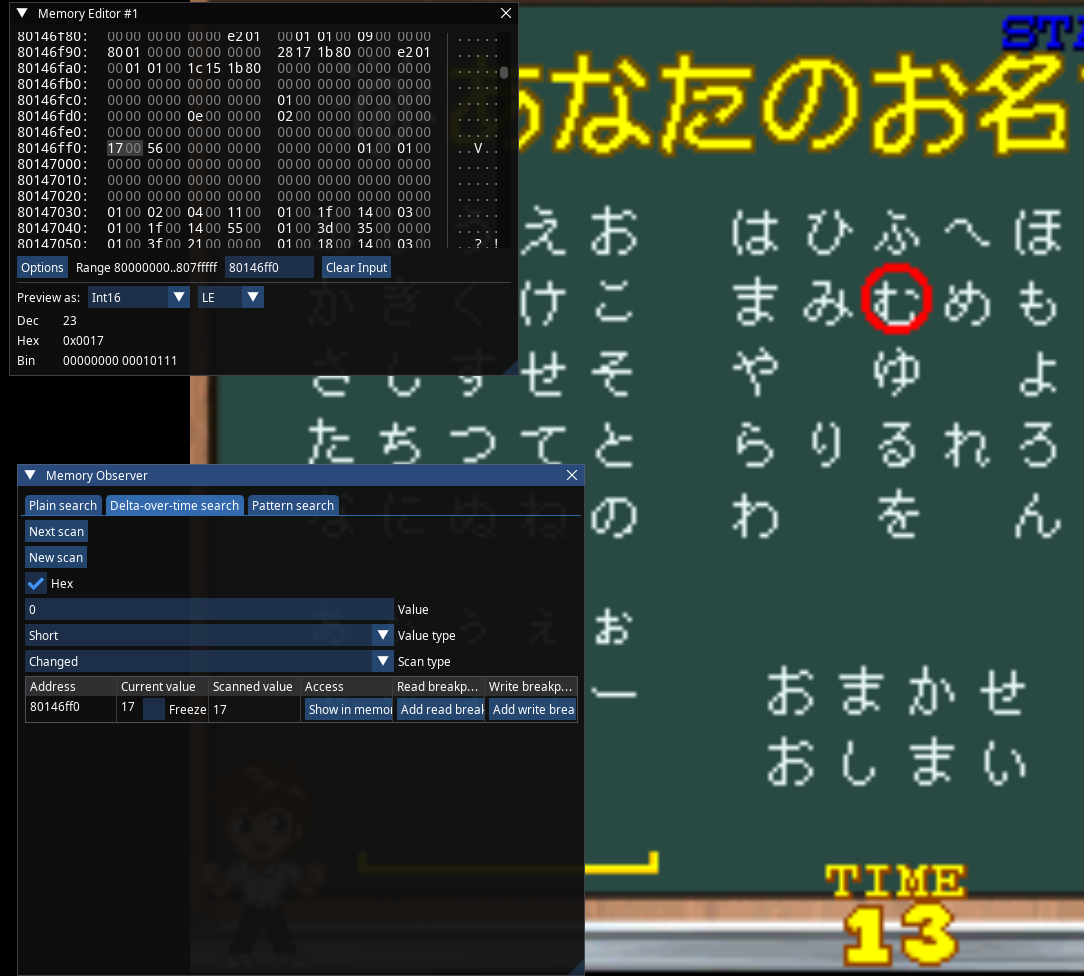

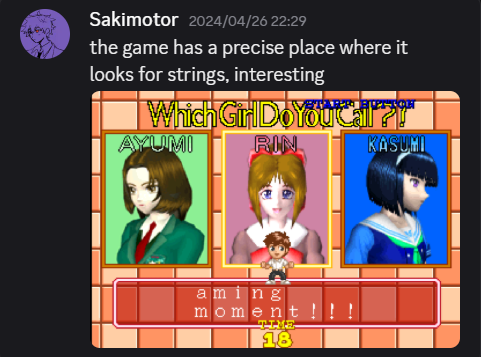

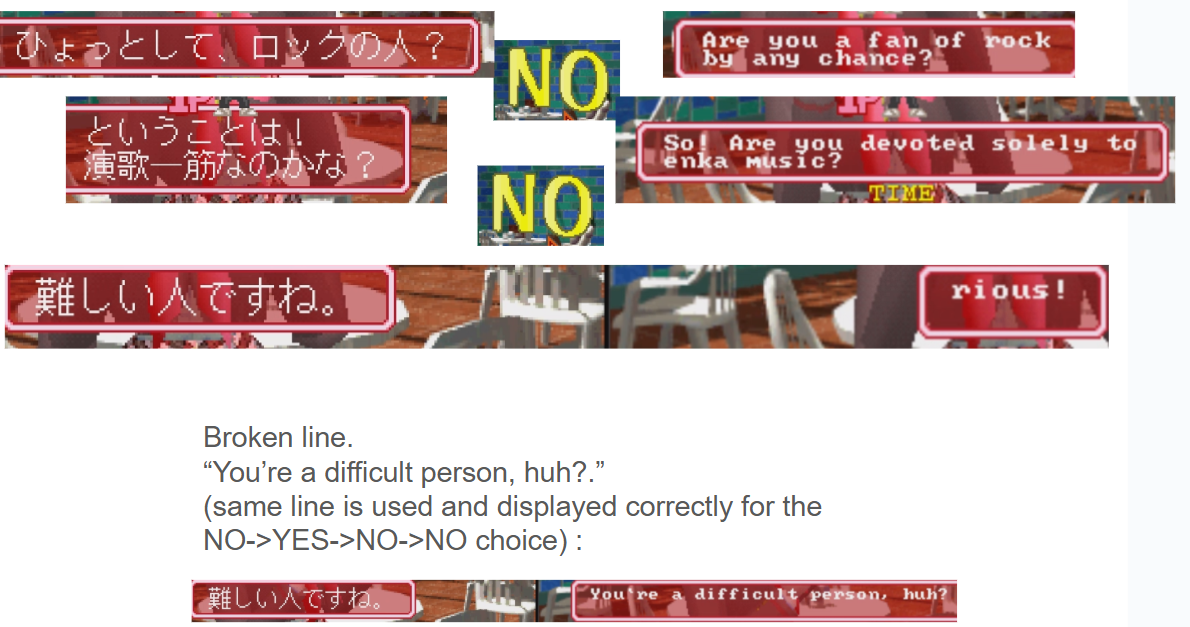

I started looking for a Hex Editor which would display the japanese strings directly, as my goal back then was just to find the text and see if it could be edited to English. HxD Editor might be nice, but it only supports ASCII. wxMEdit on the other hand was just what we needed. It took me 5 whole days to successfully display "English" letters ingame, partly because I was too dumb to realize I was editing the text too late in-between my attempts on the fly, but also because ASCII was not accepted by the game's code, so I had to use full-width characters, which would obviously not be suitable on the long term. Yes, at this point I was yet to rebuild any iso, I was still loading save states and editing the memory on the fly, byte by byte, which was a tremendous waste of time.

After a whole week of not touching the game and focusing on my studies (and other video games), I was asked by Clair to try inserting some of the edited graphics back into the game. It took some time getting familiar with img2tim, but we eventually made it (yes "we", Clair is the one who figured it out, I kept breaking the CLUT without fault). Since the game was already running, I looked more into the way it'd look for strings. Would they end on a NUL character? Yes, removing it breaks the display. Was the game looking for the byte after the NUL, or some hardcoded space in memory? Unfortunately, it was the latter, which was a sign of the game using pointers.

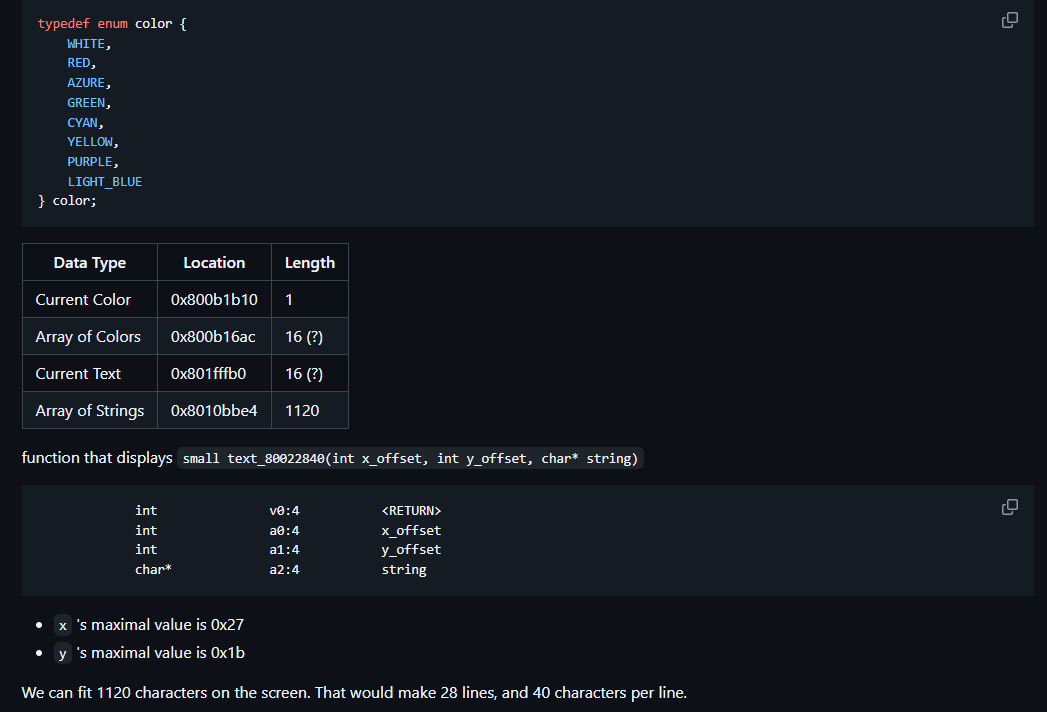

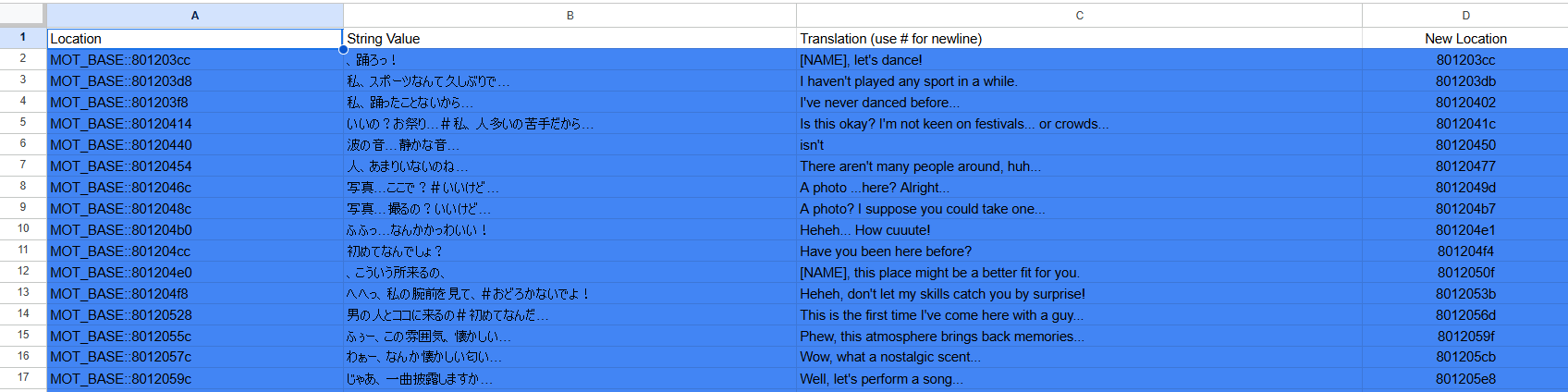

One fair assumption I've had about the game was that, just like it's the case for 99% of the console's titles, the font would be a custom one, stored somewhere as a .TIM file or something similar. I had spent days looking for it, to no avail. At some point, I had imported all of the game's overlays into Ghidra, scanned them for Encoded strings, and exported said strings into a Google Spreadsheet for Clair to translate. This meant more work (and steady progress) for Clair, and more reasons to get things done on my end (the translation can only be shown if I find a way to display half-width characters!). This also meant that I knew where all strings would be located in memory, and was able to set read breakpoints on them to tell which functions actually display the text.

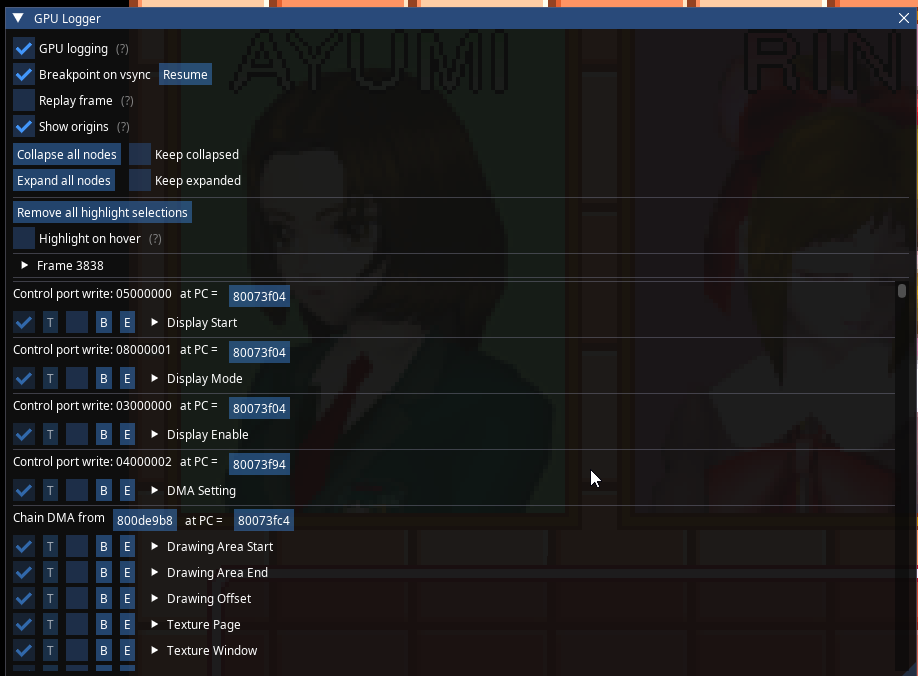

There was no end to it. I started using the GPU Debugger to see how exactly the text would be displayed, but even that was a no go... The text was summoned out of nowhere rather than taken from any font in the VRAM? I was clearly missing something, but exams were coming ahead so I took a break from the game... A little break, from my birthday on May 23rd, all the way to May 30th.

It turns out that renaming variables isn't all you can do in Ghidra; you can also make your own data structures and types. Upon realizing that, many things started clicking together on my end, And I got to understand a few more functions, mostly the ones related to CLUT manipulation, and something like blitting.

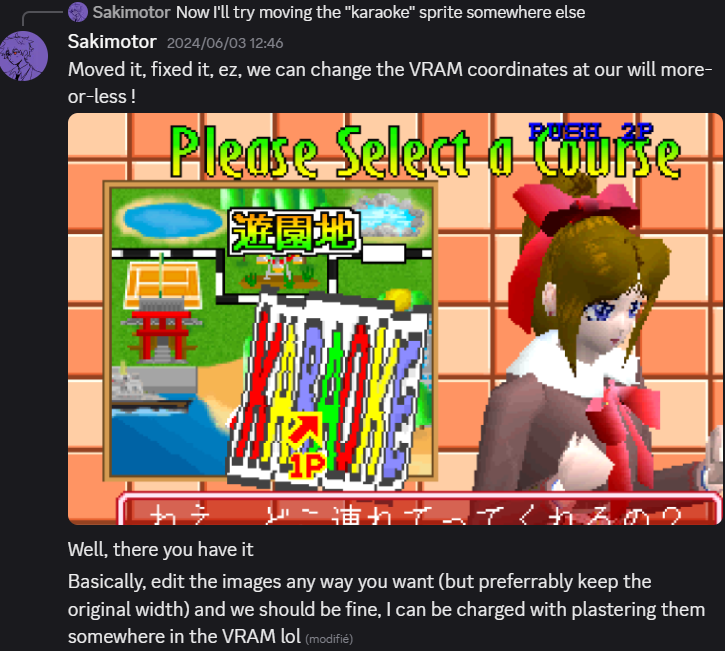

Oh yeah, I read through a whole lot of documentation related to the CLUT, the PXL, and the TIM, and it's only after days of reading that I managed to solve an issue I was giving Clair since forever: making bigger sprites was possible without breaking the rest of the VRAM, you just had to move everything around!

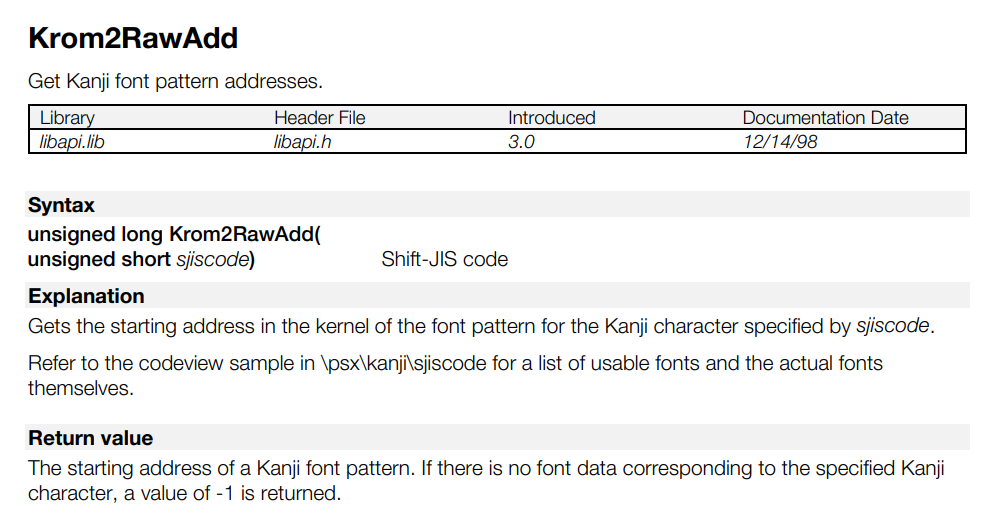

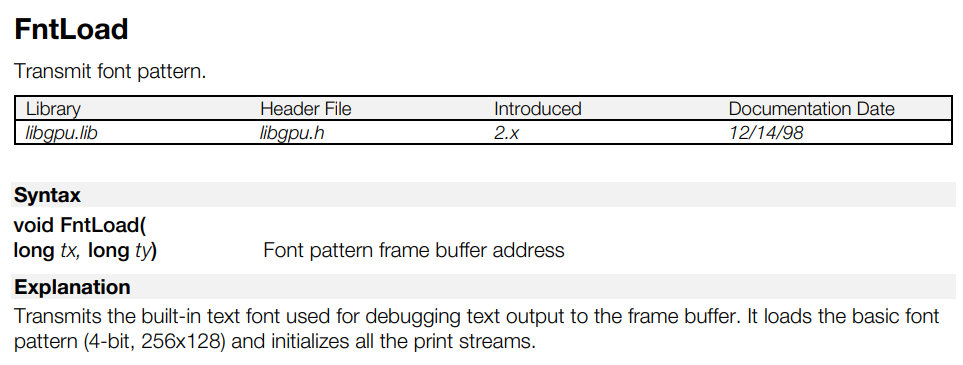

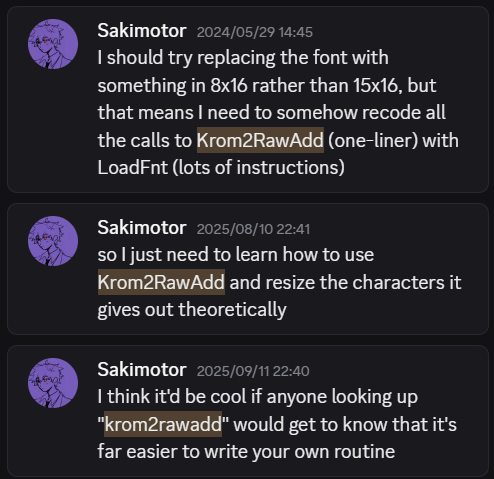

Here is another fun fact about this translation. There is actually a very obvious reason why the game's font is nowhere to be found in the VRAM: it doesn't need to be there! The font the game is using is the default SJIS font every console is bundled with, and, appearance aside, there is one function that gives it away: Krom2RawAdd. Once I was made aware of that, and the "LoadFnt" function of the PS1, I tried with all my might to bend them to my will and make them display half-width characters, or to change the game's font display routine to make the 16x16 characters into 8x8, kind of like Symphony Of The Night does it.

And thus began my obstination with the ridiculously small chunk of code that was calling the Krom2RawAdd function and pulling characters out of the BIOS to put them on screen. My tunnel vision was absolute, I HAD to figure it out and make it work in a way that'd make the English patch possible.

During those months of nothingness, I begged for help on RHDN, got some advice from PSXCraver, and wasted enough time to even involve Dimcas with my shenanigans, also begging him for help. I had tried changing the game's code so the Krom2RawAdd calls would take an ASCII character and convert it to SJIS (there is actually an example in the Psy-Q SDK that does just that), or to squeeze its' characters to 8x8 for months, to no avail. I was hopeless about the project's completion, even though Clair was able to edit all of the game's graphics completely alone by Christmas 2024 and release a first demo of the game with all of the location names and minigame tutorials/conditions translated to English.

At some point, we had found out that the game uses a small function which treats the game's screen as a 40x28 image, and reads from an array of size 40*28 EVERY FRAME to display some ASCII text (like the credit counter, or the prompt for 2P to join). This could've served as a lead, but after a few days of investigation I hadn't found where the game decides on the coordinates it'd put text in, so this idea also went nowhere.

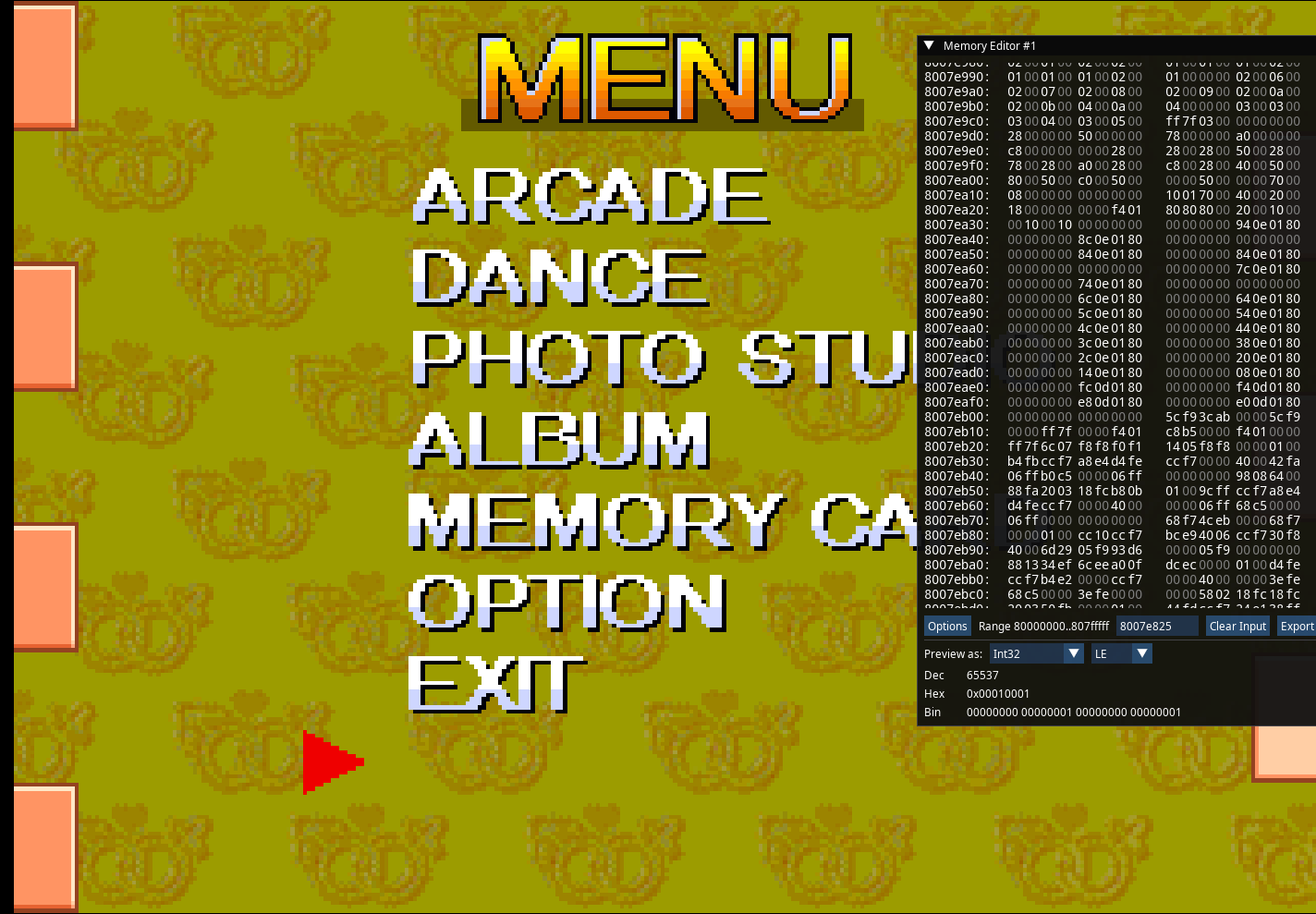

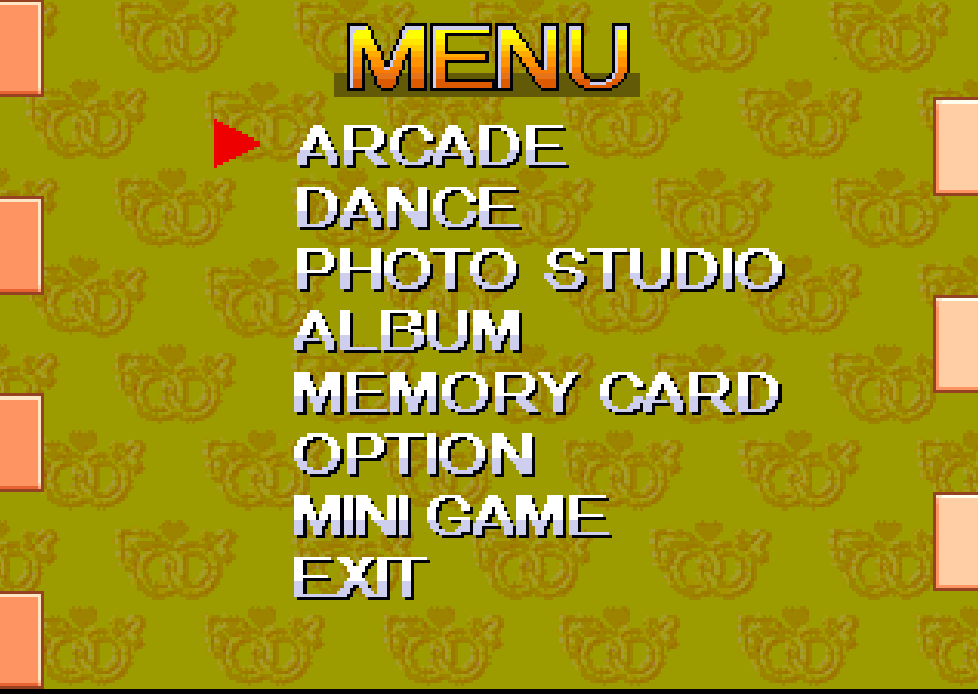

On the day before Clair's special Christmas 2024 release, I had actually stumbled upon a hidden minigame select menu. Indeed, if the byte located at address 0x8007e823 is set to 7, you could then hover an "invisible" option on the main menu, and selecting it will bring you back into attract mode. Next time you'd insert a credit, you'd be sent to the same screen as before, but with a new option: "MINI GAME". We decided to not toggle this byte on by default even if it would be "easy", as that would add more sprite editing work for a hidden feature. Said feature was used to quickly test some minigames' tutorial graphics for the 2024 Demo, then never again.

The answer to my hurdles was actually the one Hilltop gave in his video from the beginning: rewrite the font display routines and get in control of what the game does and how. I had a few reasons to not wish to go this route...

First of all, that would require finding enough free space in the RAM to welcome my custom routines. There was clearly not enough room as-is, so my only hope was to

write a function that could display some text by using far less instructions than the original one. I took many shortcuts, but surprisingly enough managed to do just that. Getting rid of some SJIS-specific shenanigans

that had no place in an ASCII-specific routine, notably the management of two bytes at once rather than one at a time, made things a lot easier and shorter. At first, I tried pulling it off in assembly, but

somewhere along the way I decided to compile my C code and test it by injecting it into the game's code in real time with the PSX Modding Toolchain, and

never looked back.

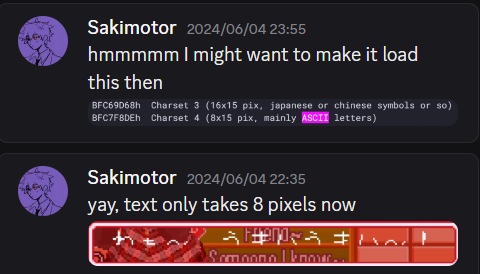

The second reason was that I needed to find a suitable 8x8 font, then a spot both in RAM and VRAM where I could fit said font. By some miracle, there were 8 pixels in width and about 100 in height left for the VRAM,

just enough to fit a 32x112 grid of symbols with 4 bits per pixel. As for the location where I'd store my font... That one is actually funny.

It turns out that retail games all start playing around with the VRAM starting from 0x8001000, because anything before that is supposedly reserved by the BIOS. Yes, supposedly. I tried my luck and pasted the font file some

hundreds of bytes before that point, and to my surprise the game didn't break on the emulator I was using, nor on PS3 (yeah after a year of nothing I had at least learned to rebuild the ISO and send it to whatever console).

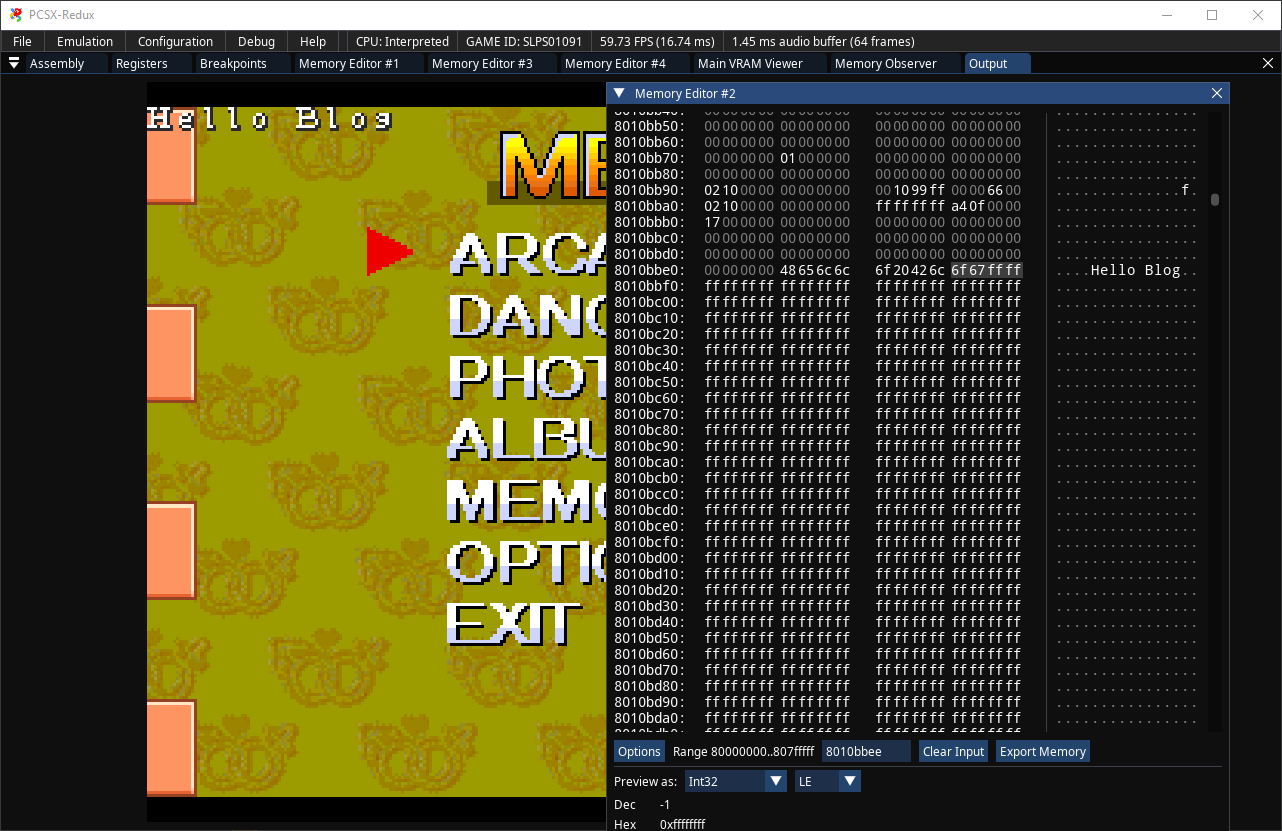

There was one final hurdle: for some reason the game only takes pure white fonts, so outlines and fancy fonts were out of question, but the default IBM font would do the trick. And thus, after a year and a trimester of pure void,

on the wonderful day of 9/11, or September 9th, progress was made.

The final reason, the silliest of them all, was... Cutting losses. I had spent a whole year trying to understand the game's mysterious font display function, surely if I had stared at it just a bit longer something

would've clicked for me, right? But enough was enough, I had to change my ways, and it definitely was for the best. Yes, had to, as it turns out Clair was done translating all 1000+ of the game's lines before I could edit them in.

Well, now that English text could be displayed ingame, in a half-width 8x8 format, it's time to edit all of the Japanese with English. We still had to figure out how does the game handle the player's name and honorifics, but that sounded approachable now that we overcame the biggest obstacle. The spreadsheet we had created conveniently stored the game's text locations, so theoretically I would've just had to copy the English where the Japanese text currently was expected to be. Of course, as it turns out, English often takes up more space than Japanese, and even though a single kanji takes up 2 bytes, we would more often than not go beyond the original text's scope. And so now, it was a cat and mouse game: we had to insert text into files, then edit the pointers referring to said text until everything would click together. Sounds easy on paper, in reality this took months and required a lot of testing. Also sometimes it wasn't pointers but arithmetic instructions in assembly :D

We've made a lot of last minute changes, mostly graphical ones so Clair was the one behind them, but some were more technical.

The honorifics and playername issue was solved around mid-September by resorting to a custom flag which would fetch from memory the last used named and honorifics (those had a permanent storage) whenever the byte 0x83 would be encountered.

Until early October of this year, the "RANK UP!" message was broken... Because I hadn't preserved the rightful CLUT. I needed to learn how to use some new program known as TIM Tool (yes, like the dozen other TIM Tools).

A few weeks before release, some dumb fuck complained about how the title screen should be in English. So, Clair was sent back into the mines, and after a couple days of pixel-by-pixel editing, we got the nice logo you all know and love today.

Until about a week before release, we still had issues with broken CLUTs for a few sprites (and yes you guessed it, Saki in person was the one behind them).

Until a few days before release, a lot of the game's lines were still broken due to unedited pointers

Very early before release, the same dumb fuck complained about the font not looking PS1 enough, so we sent Clair back into the mines, and also finally replaced the playername-related font with our own for the occasion.

What can I say ? It was a great project, with a great team,11/10, would do it again. I don't actually know what I'd work on next or who with, but one thing I can tell for sure is that Clair is a very nice and dedicated partner. Dimcas helped out a lot, and so did Rapa, many thanks to them once again. As for myself, I'm decent probably, I don't know. Truth be told, there are 2-3 other projects I'm supposed to contribute to as of now, but I'm just not able to bring that level of commitment or use to any of them, iykyk :c

In all seriousness, this was a wonderful translation project and I truly feel honored for having been part of it. I learned a lot, and hope to see through more romhacking stuff, whether it'd be on PS1 or somewhere else! I always try to learn new things, and enjoy myself as much as I could in the process. This post ended up not being as informative as I would've thought, everything flew by pretty quickly once all the elements were in place, but that's kind of how it went down from my point of view so it's probably better to keep it this representative.

Do not fear the assembly, there are many ways to compile from C into your favorite machine's assembly nowadays! Do not fear the debugging, there are many tools and emulators you can work with in 2025! Do not fear the reverse engineering, it's hard to jump into a program's "code" without any lead at first, but it's just like playing a metroidvania, easier as you discover more and more of the (memory) map!